Circular Cities

Circular Cities

Because national definitions of urban and rural areas differ significantly from one country to another, it is difficult to compare these areas across national borders. If we can’t compare the performance of urban or rural areas across national borders, then we can’t learn from policies used in other countries. It also means we cannot meaningfully compare the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals’ (SDGs) indicators for urban and rural areas across countries.

, the Degree of Urbanization seeks to define the Degree of Urbanization. (Source: World Bank)

The Degree of Urbanization identifies three types of settlements:

1. Cities, which have a population of at least 50,000 inhabitants in contiguous dense grid cells (>1,500 inhabitants per square km);

2. Towns and semi-dense areas, which have a population of at least 5,000 inhabitants in contiguous grid cells with a density of at least 300 inhabitants per square km; and

3. Rural areas, which consist mostly of low-density grid cells

Circular Cities

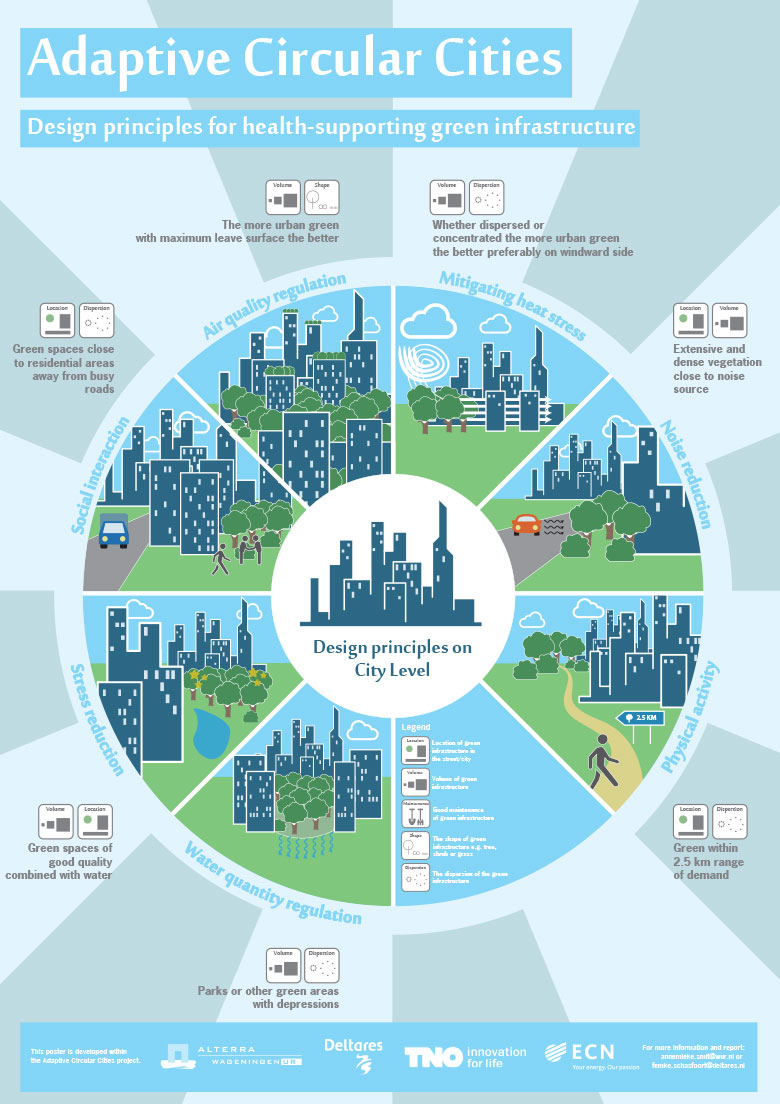

More than 80% of global GDP is generated in cities, which therefore makes them ideal testing grounds for circular economy models. The confluence of business, resident and government actors creates live innovation labs for addressing the complex challenges of linear economic models. The rich ecosystem of producers, consumers and intermediaries, as well as the goods themselves and the constant flow of information, create an opportunity to introduce new practices, including facilitation of the reverse logistics sector, material collection, waste processing, energy and natural resource conservation and new business models and product design that incorporate circular thinking.

Densely populated cities operate in a resource-constrained environment where implementing circular practices can result in immediately visible benefits, such as cost savings in the private sector. Further, cities’ practical and physical proximity makes it easier to implement policy changes than at a state or national level, where bureaucratic structures and legislative timelines can hamper institutionalizing novel circular concepts. Therefore, cities can be more agile and adaptive when implementing pilot initiatives, allowing them to stimulate change faster.

A circular city encourages the use of systems thinking to provide economic, social and environmental benefits for its citizens, while also looking to improve the quality of life.

Cities can follow seven principles in its transition towards a circular economy. These principles can be extended to define a vision and an action roadmap on circularity in cities:

- Closed-loop – all materials enter into an infinite cycle (technical or biological).

- Reduced emissions – all energy comes from renewable sources.

- Value generation – resources are used to generate (financial or other) value.

- Modular design – modular and flexible design of products and production chains increases the adaptability of systems.

- Innovative business models – new business models for production, distribution and consumption enable the shift from the possession of goods to (use of) services.

- Region-oriented reverse logistics – logistics systems shift to a more region-oriented service with reverse logistics capabilities.

- Natural systems up-gradation – human activities positively contribute to ecosystems, ecosystem services and the reconstruction of “natural capital”.

(World Economic Forum 2018 report: ‘Circular Economy in Cities: Evolving the Model for a Sustainable Urban Future‘)

Knowledge Centre

This section includes a reasonable number of reports and an eclectic mix of information on smart cities, local government, ICLEI, Building the Future plus articles and infographics.

References:

- Cities image: Freepik from Flaticon

- Knowledge Centre: Freepik from Flaticon

- Information: CleanPNG

- Links: Icon Finder

- Video: Freepik